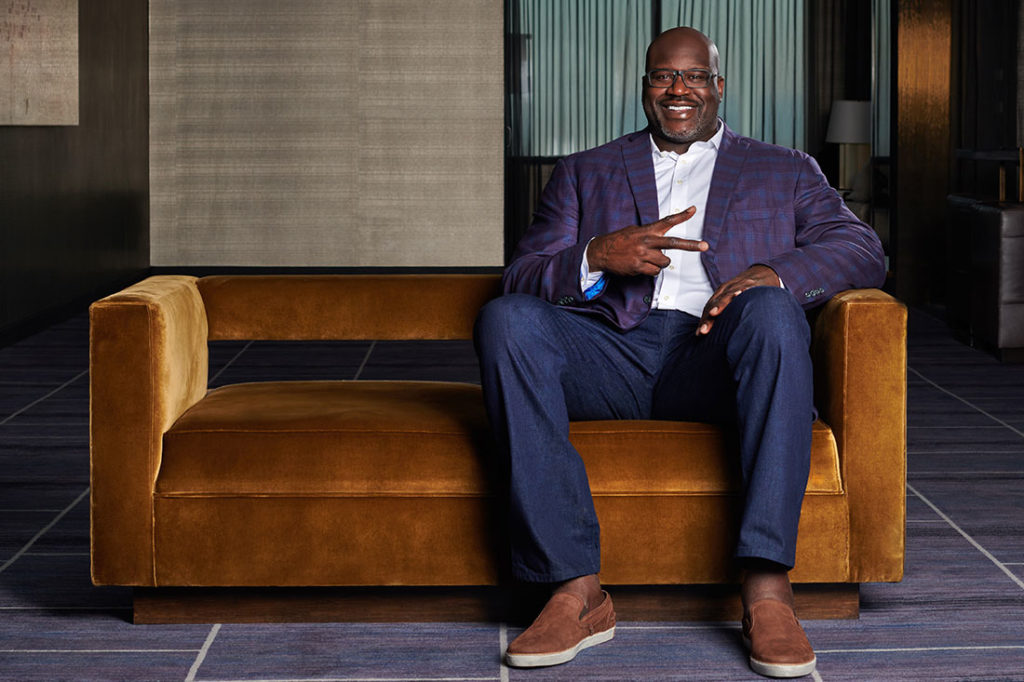

Shaquille O’Neal has been a lot of things: A four-time NBA champion, a 15-time All-Star selection, a movie star, a businessman, a rapper and DJ, an analyst on TV, an ubiquitous corporate spokesperson, even a police officer.

But there’s one thing he insists he is not: a celebrity. Like a prince giving up his royal title, he says he’s renounced his celebrity status.

“Celebrities are all crazy,” he says. “These people are out of their freaking minds. I don’t like the way they act. The things they say, the way they treat people. I don’t want to be looked at like that. So don’t call me that anymore.”

We don’t have time to get into who he’s talking about specifically before he tells me his preferred nomenclature: He says he’s actually—his words—“a regular person who listened.”

Of course, the idea that Shaq is regular in any way seems laughable. He’s 7-foot-1, more than 350 pounds, easily the largest person I’ve ever met. Jimmy Kimmel once called him “the only human visible from space.” A few hours before he arrived for our meeting, I witnessed people lining up to take photos with his shoes—each of which is roughly the size of an infant. Not to mention the fact that he’s a mononymous, legendary athlete, worth hundreds of millions of dollars. Shaq might be the most recognizable person on the planet. He can’t walk 10 feet on any sidewalk in America without someone shouting his name or asking him to pose for a photo.

I ask him how he could possibly think that he’s a regular person.

“I do regular stuff,” he tells me. (Except he doesn’t use the word stuff.) “I don’t have an entourage. I don’t have security. It’s just me.” I must look incredulous, because he keeps going. “I order random things from Amazon. I shop at Walmart—it’s my favorite store.”

Like so many Americans, he says most days he watches reruns of talk shows and reality TV (his favorite is Maury). At one point after his divorce, he even used a dating app. But the first woman he chatted with didn’t believe he was really Shaq and refused to meet.

“Shaq would never be on this,” she told him.

He’s telling me this on the 50th floor of the Four Seasons in Atlanta, in a penthouse surrounded by panoramic views of downtown. It’s also the week of Shaq’s 50th birthday. He walks a little slower than he used to, and he has trouble crossing his ankles or arms. He’s been feeling reflective recently, watching old footage and recalling old stories for a documentary being made about his life. So he’s ready to talk about everything from his childhood to his family to his own mortality. But first we spend a few minutes on this “celebrity” thing. He’s adamant.

I ask if he’s OK being called an icon—a label that seems, frankly, inarguable. There’s literally a statue of the man outside the basketball arena at his alma mater, Louisiana State University. But Shaq shakes his head.

“No,” he says in that ultra-deep voice that’s become so familiar to so many people over the years. “I’m just a regular person who listened,” he says again. “Just because I made it doesn’t mean I’m bigger than you. Just because I have more money doesn’t mean I’m better than you.” What started as a goofy conversation now feels more profound.

Finally we settle on popular. He nods. “I like to make everyone smile,” he tells me. “The world is crazy right now. If I can make someone smile, I want to make that person smile.”

As we’re talking, his longtime stylist, Renee, comes over with a massive suit jacket she thinks Shaq could wear for his cover shot. She holds it up for him to consider.

“That ain’t my jacket, Renee,” he says.

“It is your jacket,” she says. It’s massive, big enough to be a blanket for most people.

“I’m gonna show you it’s not my jacket,” he says with a wry grin. Then he grabs it and slips his arms through the sleeves.

“No! No! No!” she says, laughing. Clearly Renee’s seen this before.

I expect him to try to button the front of the jacket, possibly to demonstrate that it’s a little snug. But that’s not what Shaq does. Instead he clenches his giant fists and flexes his supersized arms and chest—and in a blink, the seams in the shoulders explode like they’re spring-loaded, leaving a giant tear from collar to hemline.

* * *

A few years ago, Shaq shared his idea for how to save gas with a national TV audience. He was on the set of Inside the NBA, where he’s been an analyst since 2011, the year he retired from his playing career. He told fellow analyst Kenny Smith that instead of filling up his tank for $80 once a week, he could stop when he gets down to half a tank and put in $20 worth of gas.

Smith, seeming confused, replied: “I’d have to stop more often.”

Shaq shook his head. “No you wouldn’t,” Shaq explained. “When it gets to half, put in 20. Then when it gets back to half, you put in 20.”

“It’s the same amount of gas!” Smith said, verging on exasperated.

“Kenny,” Shaq said, calmly. “Nobody travels more than me.”

Smith started a thought, “So if every day—” and Shaq cut him off.

“You don’t have to put gas in every day!” Shaq exclaimed. “Don’t play me right now.”

At the other end of the set, Charles Barkley was doubled over laughing at the ridiculousness of the argument. The show’s host, Ernie Johnson Jr., was leaning back with his hand to his brow, befuddled by the whole interaction.

Over the next few days, the clip went viral on Twitter. It’s spawned a series of animations, explainer videos on YouTube and follow-up discussions—each of which essentially just rehash the same argument. Honestly, I’ve watched the clip at least a dozen times and I have no clue what Shaq’s talking about, but it’s hilarious. A group of multimillionaire former basketball players talking about something that has nothing to do with basketball, and it’s not immediately clear if Shaq is some sort of mathematical genius or just playing around—and that’s the point. In any other circumstance, a conversation like this would be intolerable. But with Shaq, it’s a reason why the show is without a doubt the best sports commentary program on TV.

A lot of people could dissect the nuances of the game—and Shaq certainly does that, too—but he also brings something else. Some sort of subtly sophisticated, self-deprecating fun. It’s the same thing Shaq brings to every business or product he’s associated with. And he’s associated with a lot.

In addition to his TV gig, he also hosts a podcast, The Big Podcast with Shaq. Shaq has his own brand of sneakers, suits, eyeglasses and jewelry. He has real estate investments all over the country. And a series of children’s books. Oh, and he’s a cop. He’s been deputized in at least five different jurisdictions, and when I ask about the Glock 45 he carries in his waistband, he flips open a badge showing he’s a major with the Henry County Sheriff’s Office.

He’s also a public spokesperson for a countless list of companies, including The General car insurance, Gold Bond medicated powder, Icy Hot topical ointment, Carnival Cruise Line, Ring doorbell cameras, Oreo cookies and Krispy Kreme doughnuts. Nearly every commercial is just Shaq being, well, himself: Shaq installing a security system, Shaq dancing to the Gold Bond theme song, Shaq standing in a cruise ship pool with his clothes on. Each ad has that same element: Shaq-style fun. It’s hard to pinpoint exactly why, but no matter what he’s doing, seeing him makes you feel like smiling.

Making people smile, he tells me, is his biggest goal in life. When he eats at restaurants, he leaves famously humongous tips. (He’s been known to give a server $4,000 if the food comes fast enough.) On days when he’s not working, he goes to a Walmart or a furniture store and, as he puts it, “blesses” total strangers—with a grand or two in cash. No cameras. No media. Just a giant human creating unforgettable moments in the lives of other people.

“Especially kids,” he says. “I always try to give kids my secret.”

What is his secret?

“I tell them to always listen to their mommy and daddy,” he says. Sometimes he delivers his message while buying a little kid a new bike or handing a teenager a new iPhone. “I tell them, ‘Your mom and dad can help you more than I can.’”

When he finds out I have an infant at home, Shaq takes my phone, opens the camera, turns it to selfie mode, and starts recording a message.

“You don’t know me,” he says to the camera. “But you know this man.”

He points the camera at me, then back to himself.

“Let me tell you,” he says. “He’s a superhero. One day we were walking down the street and some bad guys jumped off a building and your daddy beat them up. Your daddy kicked them and he punched them and he threw them out of the way.”

Then Shaq raises one eyebrow and gets just a touch quieter.

“Your daddy’s a superhero,” he says. “Make sure you always listen to him.”

* * *

It was a different birthday. He was 28, in his fourth year on the Lakers, and they were playing against the Clippers on the second night of a back-to-back. Shaq was so dominant that game it was almost disrespectful. Aided by a young Kobe Bryant, Shaq raced up and down the court, grabbing his own offensive rebounds and slamming the ball through the rim so hard the room seemed to quake. He finished with a career-high 61 points and 23 rebounds in the midst of what would be his only MVP season. A few months later he won his first of three consecutive NBA championships.

As a player, he was known for his freakish physicality and athleticism—the so-called “Hack-a-Shaq” defensive strategy was so popular it has its own Wikipedia page. But he also became known for his off-the-court personality. He recorded rap albums, one of which went platinum. He appeared in movies like 1994’s college recruiting drama Blue Chips and 1996’s kid-friendly Kazaam, where he played a wise-cracking, emotional genie. He dubbed himself “The Big Aristotle.” Then told people he wanted to be called “The Big Shakespeare.”

For most of his career, he was driven by doubters. The adults who told him he’d never make it out of Newark. Coaches who told him he’d never go pro. Commentators and former players saying he couldn’t win a ring. And while yes, he was obviously domineering physically, he was also a student of the game.

During the All-Star Game this year, after Shaq was named to the NBA’s 75th anniversary team, he spent nearly five minutes listing some of the people who shaped his career. He thanked his mother, who raised him on a secretary’s salary when his biological father left them. He calls her “the great Lucille O’Neal.” He thanked his stepfather, Phil Harrison, who took him to his first pro game—where he watched Julius Erving throw down and get the crowd into a frenzy. He cited Magic Johnson, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, David Robinson, his friend Charles Barkley. He thanked people who offered advice, who helped him persevere. Coaches, executives, opponents, legends of the game.

Shaq tells me he was also driven by the desire not to be part of what he calls “that stat”—the 60% of NBA players who go broke within five years of their final game. As a not-so-subtle warning, his stepfather, a drill sergeant, used to tell him about athletes who’d lost all their money.

It’s clear that motivated Shaq to become a student of big business, too. He quotes Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates. He bought Google stock on the first offering, when the company was valued at $100 million. Today Google’s parent company is worth more than $1 trillion.

Shaq calls himself a “master of the joint venture.” Most of his endorsement deals don’t involve a large exchange of cash. Instead, Shaq usually gets an equity stake in the company, then helps it grow. And he only partners with products he personally uses and likes.

Ring is a good example. A few years ago Shaq needed a security system at a new house. The quote from a company was something like $40,000. Instead, Shaq bought himself a Ring doorbell camera for $300 and installed it himself. He loved it so much he sought out the company’s founder, which is how he ended up starring in Ring commercials. It’s not clear how much of the company he got, but Ring recently sold to Amazon for $1 billion.

He tells me he’s made mistakes over the years, too. The restaurant developers behind Planet Hollywood recruited Shaq, along with Joe Montana, Wayne Gretzky and Andre Agassi, to invest in a sports-themed restaurant chain. In a few years, the company was bankrupt. Another company he was part of in 2021 lost two-thirds of its value just a few months after going public. He says he turned down an offer from Starbucks CEO Howard Shultz because he didn’t think Black people drank much coffee.

“Now there’s a Starbucks on every corner,” he tells me.

He thinks of each mistake as a learning opportunity. He’s actually been thinking about these types of things since at least his days at LSU. When a marketing professor asked the class to develop products they could imagine selling in the future, Shaq created an elaborate plan to sell Shaq shoes, Shaq socks, Shaq shirts. But he says the professor gave him an F, noting that in the NBA, big guys hadn’t historically been great salesmen.

“He actually embarrassed me,” Shaq told HBO’s Real Sports a few years ago.

It was true, though. Forwards and guards like Michael Jordan, Larry Bird, Magic Johnson all had successful endorsement deals. But giant centers didn’t move shoes. As Wilt Chamberlain once put it: “Everybody pulls for David. Nobody roots for Goliath.”

So Shaq started studying commercials, thinking about which ads he liked and why. He remembers seeing a series of Bud Light commercials featuring a dog named Spuds MacKenzie. They were funny. He knew he could be funny.

“I’ve always been like that. I was always the class clown,” he tells me. “I almost got kicked out of high school for that. Now I’m making money doing this stuff!”

* * *

It’s strange to think of Shaq as a 50-year-old, partly because he prides himself on being a big kid. But the years of getting hacked on the court night after night have also taken a toll. He lumbers as he walks and has a hard time bending over to put on his shoes. He showed up to our meeting wearing a boat-size pair of TOMS canvas slip-ons. He says his biggest fear is getting older.

“Isn’t aging better than the alternative?” I ask.

“Not necessarily,” he says. He’s looked into some anti-aging concepts.

I ask if there’s anything he hasn’t done yet that he wants to. He says that one day he’d like to spend a year on a yacht, sailing around the world. Then he points out at some of the tallest buildings in the Atlanta skyline.

“This stuff.”

He says he wants to do more in commercial real estate. He’d like to own some buildings like these at some point, and that he’s learning as much as he can from people he knows who’ve done well with projects like that. His motivations are a little different these days.

“I want to continue to be successful,” he says. “Continue to show my kids. Continue to show other kids.”

I ask if he’ll ever run for office.

“Never,” he says. “I only want to make people happy. In politics you make some people happy and some people unhappy. I don’t do politics.”

He says he likes to balance the negative things in life.

“It’s terrible things,” he tells me. “I want people to see my face and know it’s cool. You’re having a bad day, you see me, it’s cool.”

We know now that a lot of people who work hard to make others laugh are hurting inside and use that laughter as a salve. Being the Big Aristotle, the Big Shakespeare can’t always be easy. As we head to the elevator at the end of our talk, I ask him if he ever stops to enjoy the life he’s built.

He tells me that he’s “programmed not to be happy.”

When he was a kid, he says, he’d win a trophy on a Friday, his stepfather would set it out somewhere, then invite people over for a cookout and show it off. But then on Sunday, the trophy was gone.

“I’d say, ‘Hey, where’s the trophy?’ He’d say, ‘Get another one.’”

Shaq says that mentality forever propels him.

“It keeps me grounded,” he says. “That’s actually why I won three straight championships. After the first one, I was like, ‘I’ve got one, I’m cool.’ Then I hear, ‘I bet you can’t get another one.’ Then ‘Magic and Kareem got two, I bet you can’t get three.’”

He says it drove him crazy.

“After all this time, I fought for respect, and you still don’t respect me? Watch this,” he says. “When you grow up and they tell you that you’re nobody, you thrive on being somebody.”

That’s why he played 19 years, always hungry for another ring. It’s why he’s convinced there’s always another business deal. And it’s why there’s always someone else he can make smile, just by being Shaq.

It’s not too bad—for a regular guy who listened.

This article originally appeared in the May/June 2022 Issue of SUCCESS magazine. Photography by Bianca Pierre.